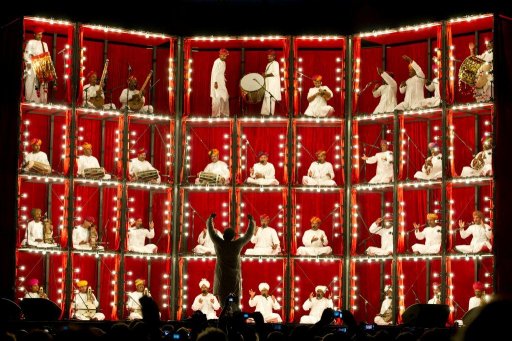

Photo: Matt Crossick

Happiness or art?

The Cultural Value Project examines the value of the arts and culture rather than just its outcomes – and its negative effects. Patrycja Kaszynska introduces the project.

Let me start with a thought experiment. Isn’t the choice between happiness and art – the famous dilemma of Huxley’s Brave New World – a no brainer? Apparently not. Some might go for the easy choice but many would flinch and quiver before reluctantly choosing to sacrifice individual happiness. This is telling. The fact that Huxley’s provocation remains a genuine dilemma tells us something about the value of art and culture to our society. This value is difficult to pin down and yet distressingly incorrigible.

The Cultural Value Project was established to face up to the problem of cultural value. Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and led by Professor Geoffrey Crossick, the research initiative’s objective is to advance how we understand and define the value of cultural engagement to individuals and society, and to refine the methods by which we evaluate that value. To this end, the project is supporting nearly 70 academically led, individual projects. This research will bring together other existing analyses and evidence to be published in 2015.

There is little evidence that the arts and culture make us straightforwardly good or bad

The goal is to achieve an enhanced understanding, not an improved advocacy. For many years the debate over the value of arts and culture has been dominated by the imperatives of those wishing to make a stronger case for public funding. In practice, this has led to a fixation on economic impacts – frequently speculatively attributed rather than empirically demonstrated. This in turn has resulted in a ‘crisis of faith’. These arguments simply no longer persuade the funders, nor the cultural sector itself.

The intention of the project is to avoid repeating past mistakes. As we wrote in the Introduction to the Project, “The Cultural Value Project does, of course, wish in the medium term to influence decisions on public policy and funding, but its priority lies in developing a much better understanding of arts and culture across the diverse ways that they are organised and experienced.” For this reason, we have broadened its focus beyond the subsidised sector to include the commercial sector, voluntary arts and home-made culture. Hopefully this breadth of scope will allow it to engage the question of cultural value as a genuine research question and not merely an issue for the next spending review.

From the outset, we have insisted that the term ‘evaluation’, not just ‘measurement’, be used in relation to cultural value. Quantitative and qualitative approaches should be of equal status provided they are used rigorously. In short, different methods and techniques may be appropriate for different forms of evidence. In order to respect the character of the evidence at hand we have engaged a wide range of academic disciplines: creative disciplines and the humanities, as well as cultural policy, but also the social and natural sciences. To stay sensitive to the appropriateness of the methods used we have also adopted a component approach, looking simultaneously at a number of different, mutually irreducible ways in which cultural value manifests itself. Starting with the way arts and culture engagement may lead to an enhanced reflectiveness and understanding of oneself and an appreciation of the other, as well as one’s place within the social collective, through to the role of arts and culture in stimulating international understanding and promoting health and wellbeing, and finally, looking at economic effects and urban regeneration.

We choose to talk about value rather than outcomes, mostly to stress the open-ended, relational nature of cultural value and to emphasise the importance of understanding the valorisation process, which gives rise to this value in different circumstances and forms. Basically, cultural value happens through human interaction with cultural objects and events in the context of other daily activities, and its effects are notoriously difficult to predict. (Notably, part of our effort is to understand how the valuing of culture is intermeshed with questions of social privilege and whether understanding everyday participation – how people attach and articulate value through their everyday routines such as going to a pub or walking a dog – can shed some light on how cultural value has traditionally been framed through the institutional canon.)

Furthermore, we wish to talk about values and not benefits in order not to pre-judge research findings. For many years, artistic and cultural engagement have been considered a near panacea for social ills. Yet now we know that the alleged connections between cultural activities and urban regeneration, improved educational attainment and curtailed reoffending rates have not always been properly grounded. Staying true to the spirit of unprejudiced inquiry, we want to register the range of negative effects that culture can have. It is time to face up to the fact that art can serve to support and mobilise hostility and mistrust, most notably when deployed to serve propaganda purposes, but also through engagement with certain kinds of national assertiveness or hostility between ethnic, religious or other communities.

The overarching aim is to capture as accurately as possible what happens in actual encounters with the arts and culture. We need to get to the heart of the experiences and to appreciate what effects follow, rather than simply inferring this from the ancillary, instrumental effects of these experiences. In this sense, a wider ambition is to question the inherited discourse: its assumed distinctions as well as its elisions. One such distinction is the unhelpful schism between the instrumental and the intrinsic. The questions whether the experience of art and culture is worth undergoing for its own sake or whether it is beneficial in some other ways are not mutually exclusive. In fact, it could be productive to analyse the instrumental through the prism of the intrinsic by recognising that the motivation to undergo cultural experience in the first place can stem from the intrinsically rewarding character of this experience.

Finally, many ways of evaluating cultural value, especially those developed by economists, are based on the benefits to individuals, often on the basis of their own stated preferences. Whatever the potential of such methods, it is important to recognise that these methods may struggle to accurately capture social benefits if these are more than the aggregate of the benefits to individuals. In other words, the overarching principle of consumer sovereignty underpinning these methods may be ill-applied to those instances where we are concerned with what Charles Taylor referred to as the "irreducibly social" functions of the arts and culture, and where the augmented welfare benefits cannot be attributed to individuals. And so, as part of the wider ambition of the project, we would like to try to rethink the public value of the arts and culture through the prism of the private and vice versa. It could be that the main locus of value, and one of its primary registers, is intersubjectivity: the metaphorical space inbetween individuals relating to one another.

The work done within the individual components will hopefully shed some light on what we know and what we don’t know with respect to the effects of art and culture on health and wellbeing, urban regeneration and local and national economies. We are also getting an intimation that there might be some empirically grounded evidence to allow us to elaborate more fully on how cultural value should be understood in relation to the effects of art and culture captured under the elusive heading of the ‘Reflective Individual and the Engaged Citizen’.

Some emerging themes point to a different sense of agency and empowerment triggered by cultural encounters – a feeling of being in control beyond passive consumerism. (This sense is particularly pronounced in relation to arts-based therapies in mental health and arts activities in prisons.) A renewed awareness of collectivity brought about through the forms of experiencing dictated by arts participation and engagement – the recognition of new ways of being together beyond the atomism of neo-liberal individualism – is also resonating in different strands of research (take for instance the effects of reader clubs or arts activities with disaffected youth).

Above all, what seem to be emerging are the contours of a less short-termist, individualistic understanding of the utility attached to cultural value. There is little evidence that the arts and culture make us straightforwardly good or bad and there are good reasons to think that cultural encounters make us more complex, deeper and more humane. No wonder that the stark choice presented by Huxley remains a dilemma.

Dr Patrycja Kaszynska is Project Researcher for the AHRC Cultural Value Project.

For more details of the project go to the AHRC website

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.