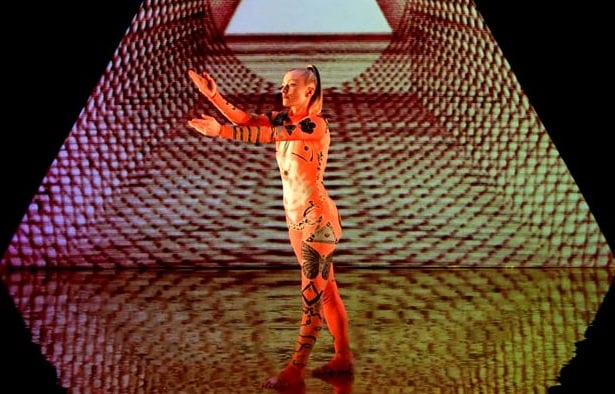

Photo: Brian Slater

Choreographing conspiracy

When choreographing a new contemporary dance work for young people, Rosie Kay committed to really listening to their concerns and beliefs – and it took the work in a surprising new direction.

Across the arts, we’re seeing a decline in young people taking up creative subjects, with dance being particularly affected. Since 2010, there has been a reduction of 32% in the number of young people studying it at GCSE level, and when we look at the broader picture of participation and attendance at events, the biggest drop is in the 16 to 25 age bracket according to the DCMS Taking Part survey for 2015/16.

From this perspective, informed by young people, I could see a fantastical mêlée of satanic ritual, the glamorisation of corpses, trances, death, rebirth…

Research from the survey also shows one of the key reasons for low engagement levels is a lack of programming and cultural offerings that are of personal interest. As artists, choreographers and theatre-makers, we need to listen to young people and produce work that they want to engage with and feel a connection to.

Youth conspiracy theories

I was pregnant when developing my latest production called MK ULTRA and immersed myself in online spaces, discovering an endless world of conspiracy theories, widely circulated by young people. One conspiracy theory that kept cropping up was that pop culture icons are groomed from an early age via a programme of mind control continued from the CIA’s (real, often illegal) mind-control experiments in the 1960s.

As soon as I started delving into this world, I quickly discovered that, when asked, young people seemingly across the board have this wealth of knowledge on subversive theories of power and control. This knowledge – because it’s rarely discussed outside these circles, let alone taken seriously – remains largely unheard of to older audiences.

Although ‘fake news’ and ‘alternative facts’ have only recently become more common features in mainstream news headlines, young people’s distrust in the media appears more deep-seated. Since I started researching the project three years ago, I’ve watched this gulf appear between the spin from traditional authorities and what young people speculate is happening behind the scenes.

I conducted extensive interviews with school students asking them to tell me about their values and beliefs around popular culture. Prompted with open-ended questions such as “What does this imagery say to you?” and “Can you describe this music video?”, discussions always led to mention of the Illuminati, an elite cult whose supposed influence dominates politics, economics and the entertainment industry.

The Youth Index recently reported that 44% of young people said they didn’t know what to believe in the media, and here I was learning how they are creating their own theories of who holds power and control in contemporary society and over individuals’ lives.

Hidden codes and symbols

The young people taught me a language of codes and symbols apparently smuggled into popular culture, specifically pop music videos. I watched and listened to Rihanna, Miley Cyrus, Taylor Swift and Justin Bieber armed with this new ability to spot telltale imagery, far from any other research process that I’d used to develop contemporary dance previously. From this perspective, informed by young people, I could see a fantastical mêlée of satanic ritual, the glamorisation of corpses, trances, death, rebirth and a mechanical version of female sexuality all hidden in plain sight.

Such were the testimonies that I gathered from the students, I ended up incorporating excerpts of their filmed interviews into the staging of MK ULTRA. Not only were their ideas crucial to developing the piece, now their voices were integral to the show’s content.

Social media characters

MK ULTRA is performed by a cast of seven young dancers. The content of the piece, in its commentary on superficiality and the tension between reality and fiction, lent itself to marketing via social media. Instagram, with its focus on sharing images and cultivating visually communicated personas, enabled the dancers to create a surreal world revealing the superficiality of their performing characters – and archetypal characters within the entertainment industry.

Each dancer has a separate account depicting the character they play. For instance, there’s the MK ULTRA queen, a naive pop cutie and a character desperate for the ‘likes’. The social media activity hasn’t been shoehorned in for the sake of it – the content ties into its promotion.

We knew in the R&D period that we’d need to ensure that the show’s marketing campaign aligned to reach the under 25s, so we wrote into the funding bid a marketing role that focused on this area. This role has overseen the social media activity and ensured that youth groups connected to each tour venue have had the opportunity to take part in the promotion of the piece.

New directions

Listening to young people – their concerns, beliefs and values – took me in a new direction with my work. It challenged the creative content that I was using, which certainly raised an eyebrow as I was describing the project in development. It may have been risky, it could have alienated older dance attenders, but artists need to listen and respond to contemporary culture.

If we want to foster arts engagement with young people, we need to have an open dialogue that values their opinions and welcomes their input in shaping creative productions.

Did it work? The London premiere sold out and I was thrilled to see many young people in the audience. We’ve had a fantastic response throughout the tour, so if there’s a key lesson to be learned from this process, it’s to listen and respect young people’s beliefs and perspectives, and allow them to turn everything you thought you knew upside down. In this post-truth era, they are in many ways ahead of the game.

Rosie Kay is Artistic Director of Rosie Kay Dance Company.

rosiekay.co.uk

Tw: @rosiekaydanceco

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.