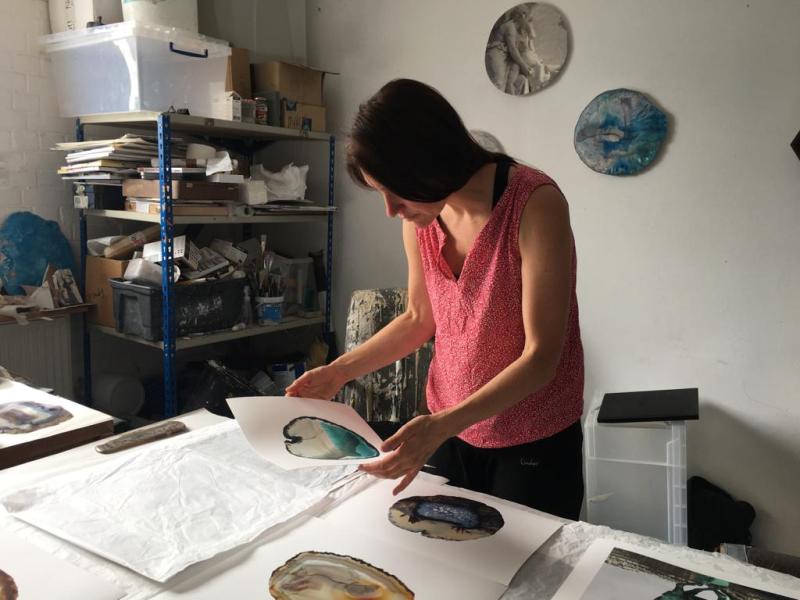

Detail of 'We're all in this together' by Liane Lange at Kunsthalle Tubingen, 2019

Age discrimination in the art world

Though opportunities for young artists may be laudable, Liane Lang thinks age boundaries are discriminatory.

Most would agree that art historians and curators have done a poor job over the past century of bringing a full and complete picture of the world’s cultural production. Rediscoveries abound of artists who were ignored over a lifetime, excluded from public exhibitions and publications but who somehow continued to produce despite the art world’s best efforts to exclude them.

These are now so numerous it can no longer be considered a marginal problem. We know who has been excluded: women, artists of colour, poor, disabled and working-class artists, foreigners. There are many mechanisms that bring about an undervaluing of artists, but there is one that exacerbates all and has been largely ignored: age discrimination.

Age is an explicit qualifying criterion in a huge number of artist opportunities – exhibitions, prizes and residencies. These opportunities may openly state that candidates must not be over 25, 30, 35 or 40 – or slightly more subtly, that they must be within five or 10 years of graduation.

Germany and Austria are particularly bad in this regard, but it happens in the UK too. There are good reasons why these opportunities exist of course, ‘supporting young artists’ and ‘hearing new voices’ being the most popularly quoted. But there are an enormous number of these opportunities and very few for the vast majority of practicing artists who fall outside these groups.

Most barely get off the starting block

Apart from the desire to support a new generation, one wonders whether attractive Instagram photos of nubile practitioners in their studio spaces is a motivating factor. Equally concerning is the commercial market’s motivation for such age discrimination: a young artist is easier to market, their work and career mouldable and they promise investment returns.

Why is this discriminatory, after all everyone gets older? It is discriminatory because how quickly and successfully we kick-start our career depends to a very large extent on criteria not connected to our artistic vision or innate talent.

A wealthy graduate can leave college, find a studio and dedicate themselves full time to their artistic practice. Taking time not only to make art, spend money on materials and equipment, fabrication and transportation, but also to apply to the plethora of opportunities available in this crucial early postgraduate period – hanging out at openings and events to meet important people.

Sculptors in particular can make large and impressive installations if they can be made and stored in granny’s barn. And high-quality materials make work more professional and valuable. Compare this to a working-class graduate. They will finish their degree with significant credit card debt and overdraft and will take several months or longer to find accommodation and part-time work to support their livelihood before they can even think about renting a studio space. This studio space will often remain unused due to the necessary extra working hours to pay for it.

Most panels for early career opportunities will never hear from these artists; they barely get off the starting block to make any work at all and don’t feel confident to apply for major opportunities.

Creating a diverse and representative culture

There are multiple scenarios that make an artist unable to start their practice until later in life. Illness, caring responsibilities, a death in the family, are only some of the anecdotal reasons my straw poll of older artists has produced as to why they didn’t attend residencies after they graduated or didn’t manage to make much work.

It isn’t hard to see how this impacts women to a much greater extent. If an artist has completed both a BA and MA, they be nearing 30 by the time they finish. I attended seven weddings in the year after graduating.

The women artists who start a family will not be attending any residencies for many years. Most don’t allow children and the expense and complexity of organising it puts most women off even trying. By the time the kids are old enough, they of course are no longer young enough, a new voice nobody wants to hear from.

Good examples when age is not a selection criterion are residencies such as the Bogliasco Foundation or the Vermont Studio Centre. Here, artists in residence can be between 18 and 80, bringing together generations, ethnicities and nationalities to spend several weeks talking about very different ways of making and thinking about art and life.

Leaving our silos and echo chambers is the most significant thing we can do against polarising and adversarial public debate. If we want to create an art world and by extension a culture that is diverse and represents as wide a range of artistic positions as possible, we must seek to avoid all forms of discrimination.

Institutions and gatekeepers in the art world should take a moment to reflect on the record of the last century before deciding whether the status quo is good enough to serve for the next.

Liane Lang is a visual artist.

![]() www.lianelang.com/

www.lianelang.com/

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.