Photo: Daniel James

The ethics of sponsorship

Choosing a multinational oil and gas corporation as the major sponsor of a climate change exhibition sounds like something straight out of 'The Thick of It'. But, says Justin Williams, Shell's corporate sponsorship of the Science Museum is no fiction.

After the sponsorship was announced in April 2020, there was an immediate backlash. An open letter written by the UK Student Climate Network warned the museum’s director that it risked huge reputational damage with the decision.

And when the world learned of the gagging clause imposed by Shell which “would prevent museum staff and trustees from criticising the oil company,” it only appeared to confirm this. In August, activists from Extinction Rebellion protested outside the museum, attaching and gluing themselves to the railings.

No sooner had the protest ended, than the institution announced another sponsorship deal – this time with a subsidiary of Adani Group, a conglomerate with coal mining operations in India, Indonesia and Australia. The announcement came in October just two weeks before the start of Glasgow’s COP26.

A string of resignations and departures followed. Chris Rapley, who was once the director of the Science Museum, resigned in October from the museum’s advisory board citing his opposition to its sponsorship policy. TV presenter Hannah Fry also stepped down as a museum trustee because of its ties to Adani.

A long history of such sponsorship

But Shell and the Science Museum is not the only cultural-corporate sponsorship arrangement to be labelled as environmentally and ethically irresponsible. In fact, these arrangements have a long history in the British culture and arts scene.

BP’s sponsorship of the National Portrait Gallery endures after 31 years, although in 2020 mounting pressure forced the gallery to drop BP’s representative on the judging panel of the annual BP Portrait Award. Seventy-seven leading artists – including Antony Gormley and Anish Kapoor – joined 2019 judge and artist Gary Hume in signing a public letter calling for the BP representative to be removed from the panel.

It’s not just the cultural sector in the UK which relies on big name sponsors to help fund the arts. Philanthropic institutions such as The Sackler Trust have donated to cultural institutions all over the world, including but not limited to: Guggenheim, The Metropolitan Museum, the Louvre and the Smithsonian. The affluent Sackler family who run the trust, pleaded guilty to criminal charges brought by the US Department of Justice concerning the firm’s marketing of OxyContin – a drug which is said to have fueled the American opioid crisis.

The value of sponsorship to the arts

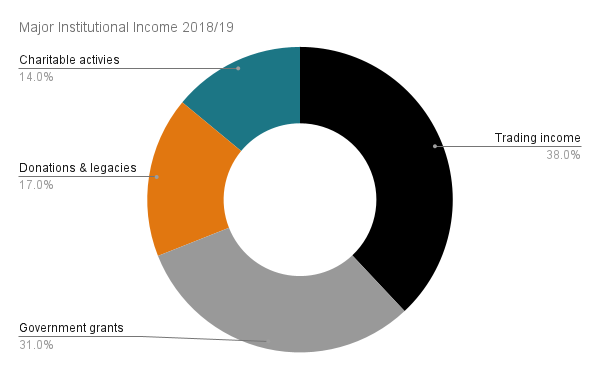

While many major cultural institutions receive a significant funding from Government, footfall and other commercial activities remain enormously important sources of income.

Based on data taken from the 2018/19 annual accounts of the major galleries (Tate, National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery), 17% of income came from donations and legacies, and 38% and 31% came from trading income and Government grants, respectively.

Ethical decision-making

Whether sponsorship arrangements and negotiations are undertaken by an ethics committee or board of governors, cultural organisations must draw up their core principles, mission and values and have a set of unambiguous ethical guidelines to follow before entering into negotiations.

If the decision-making group is actively engaged and at the forefront of ethical debate then these guidelines should be reviewed regularly in line with changing opinion, news and sentiment.

Additionally, engaging in a due diligence process before any sponsorship or activation can be crucial. An investigation into the background of the third party can reveal unexpected controversies, clarify the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed deal, and generally help an organisation assess its risk tolerance.

What accountabilities are there?

Galleries and museums are fundamentally public bodies, but they are not subject to the same structures of accountability that state organisations and agencies are bound by.

Our major cultural institutions are under scrutiny like never before, with specific policies governing ethics, whistleblower protections and environmental standards. Central and local Government also demand performance and operational indicators.

Cultural institutions exist to serve society but not individuals, special interest groups or shareholders. So they must conduct themselves on behalf of the public, holding their collections in trust for the community as a whole. This makes public trust the ultimate layer of accountability.

When this works it is because public trust has been ensured through a layered system of internal accountability underpinned by the oversight of the organisation’s governing body which is ultimately responsible for all of the institution’s financial, ethical and policy decisions.

This is then manifested publicly through transparency and the obligation to give society access to detailed information including financial, ethical, environmental and governance data.

Would the sector survive without this funding?

“Even if the Science Museum were lavishly publicly funded, I would still want to have sponsorship from the oil companies,” said the Science Museum director, Ian Blatchford, to quite a few raised eyebrows. The truth is arts and culture aren’t lavishly publicly funded.

What’s more, the pandemic has and continues to have a major impact on cultural finances. Across 2020 and 2021, many institutions were forced to close their doors, cutting off their main source of income.

It is unsurprising therefore that with this additional shortfall many are having to increase their financial reliance on sponsorship, donations and other private sources of funds.

A more ethical framework

It would be remiss to deny that there is a mutual convergence between industries that want to improve their image and an arts sector which is struggling to fund its projects. Often the companies with the biggest issues are the ones which have the most to prove and more money to spend.

While some relationships may be genuinely philanthropic and have the best intentions, terms like “greenwashing” or “artwashing” are frequently bandied about. There is no escaping the fact that these relationships can give companies powerful lobbying opportunities to win political influence.

For many institutions it would appear that this convergence is no longer mutually beneficial, as protests take place outside, fellows resign, and reputations are tarnished.

When it comes down to it, our biggest institutions stand or fall on that ultimate tier of accountability: the trust of the public. It is only through continued vigilance when it comes to ethics and transparency that that trust is ensured.

Justin Williams is Chief Operating Officer and Co-Founder at InsightX Ltd.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.