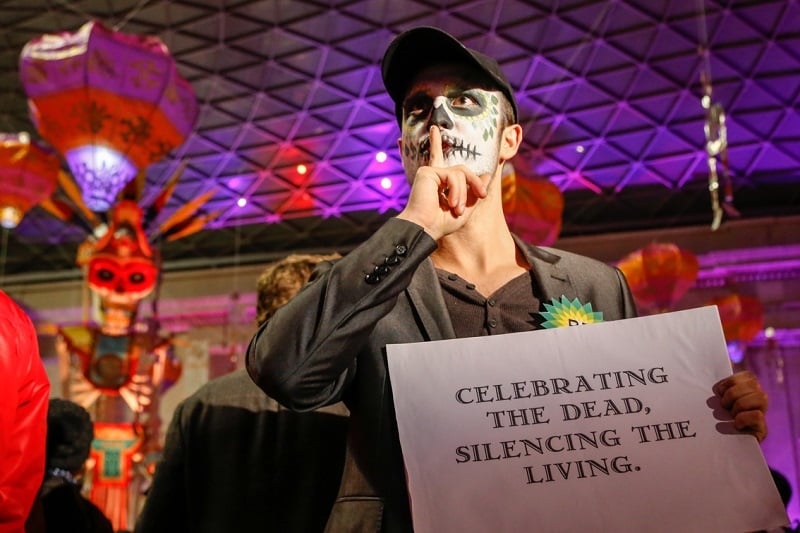

Arts activists protest at the British Museum's Days of the Dead Late event, sponsored by BP.

Photo: Diana More

Exposing ethical questions

Following revelations that BP influenced curatorial decisions at the British Museum, Chris Garrard examines how arts organisations should be navigating the tricky ethical territory of sponsorship.

The writer and playwright James Baldwin once wrote: “The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.”

Perhaps today, his challenge should not just be for artists but for museums and galleries too. Artworks and artefacts do not end at the edge of their frame or display case, but flow outwards, fusing with ethical questions of when, where and how they are displayed.

Increasingly, artists and arts organisations are being asked to reflect upon who funds their work and examine whether that funder shares their values. The motivations of a corporate sponsor are not something that should be taken for granted. But in order to do that, we first need to understand our own ethical values.

Perhaps it is by debating and devising ethical codes or fundraising policies that we can find consensus, and a platform from which we can confidently put those values into action. Without that sense of ownership, external pressures may cause us to compromise on them.

A question of accountability

Ethical consistency may seem difficult to test but, in reality, it is clear when two sets of values do not align

My recent report for the campaign group Art Not Oil revealed how BP’s sponsorship of the ‘Indigenous Australia, Enduring Civilisation’ exhibition at the British Museum caused an ethical compromise.

In an email to BP, the museum described a consultation process with indigenous communities as “the cornerstone of the whole project”. But the museum failed to ask many of the Aboriginal communities for their consent to BP’s sponsorship.

According to the museum, “consultation with communities had been completed” by that point. But in not consulting them, the museum made a tacit judgment about what it felt was in their interests and the information they should have access to.

What makes this more problematic is that emails, released under the Freedom of Information Act, appeared to show the museum asking BP if it had “any objections” to the purchase of a painting by members of the Spinifex community. When the museum later argued that this email to BP was simply an update to a sponsor, it missed the point. There should never have been any question that the museum’s accountability to Aboriginal communities could be compromised.

Transparency and respect

The Museums Association’s recently revised Code of Ethics states that museums should “build respectful and transparent relationships with partner organisations”. The words ‘transparent’ and ‘respectful’ should be treated, as far as possible, as absolute terms – is it possible to be just a bit transparent or slightly respectful?

Transparency is significant because BP’s offer of money establishes a relationship of power, and if museum priorities appear to shift, the motivations behind them should be laid bare.

When Philippe de Montebello was Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he promptly returned Chanel’s money when he felt that the sponsor was attempting to “erode” the museum’s curatorial integrity: “I simply can’t have that”, he said at the time.

Aligning values

A key development of the Code of Ethics is that it now states that museums should “seek support from organisations whose ethical values are consistent with those of the museum”. Ethical consistency may seem difficult to test but, in reality, it is clear when two sets of values do not align.

The British Museum claims to be “committed to sustainable development throughout all the aspects of its operation.” But last year, just weeks before BP was due to bid on drilling licenses auctioned by the Mexican government, it enjoyed a valuable networking opportunity with government representatives as part of the museum’s ‘Days of the Dead’ festival (a part of the public programme).

BP’s Group Regional Vice President, Peter Mather, has since conceded, “when there is an option, naturally we are going to try to match a particular exhibition with somewhere we have an interest.”

When a museum knowingly lends itself to a sponsor’s business plan, this is not an acceptance but an endorsement of the sponsor’s ethical values.

Due diligence

The Code of Ethics also highlights that museums should “exercise due diligence in understanding the ethical standards of commercial partners with a view to maintaining public trust”.

For the British Museum to exercise due diligence with regard to BP, it must be thorough. For example, following BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster, the company lied to the US Congress about the size of the leak from the Macondo oil well. Even if we put aside the impacts of the spill, BP’s values were laid bare by its actions: the pursuit of its business involved deceit and illegal activity.

It is only when we look at these examples from multiple angles that we gain a full picture of a sponsor’s ethical values.

Ethics in action

My report for Art Not Oil was in some ways an exercise of due diligence, as it sought to expose the hidden ethical questions behind the claims of BP and the museum.

The Museums Association’s Ethics Committee is currently considering the issues the report raised. They may choose to offer an opinion on alleged breaches of the code, or it could be passed to a disciplinary committee for further investigation and face potential sanctions.

But the new Code of Ethics has already demonstrated the benefits of developing a set of agreed values: it has stimulated debate within institutions, provided the basis for training and offered a framework for the public and groups such as Art Not Oil to hold institutions to account.

But any ethical code or fundraising policy should be seen as a beginning and not an end. Due diligence should mean continuing to expose new questions that we may feel uncomfortable confronting.

Art Not Oil’s scrutiny of the British Museum’s BP deal is also a beginning and not an end – it is an invitation for the museum to make its values more visible and put them into action. Dropping BP is the next logical step.

Dr Chris Garrard is a campaigner, composer and a member of the Art Not Oil coalition. He was the lead author of Art Not Oil’s report ‘BP’s Cultural Sponsorship – A Corrupting Influence’.

www.artnotoil.org.uk

Tw: @ArtNotOil

E: [email protected]

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.