Getting to grips with intellectual property

The idea of managing intellectual property fills many people with not just uncertainty but dread – which is why the Boosting Resilience programme recently explored a three-stage approach to make it less daunting.

With intellectual property (IP), lack of knowledge can be an overwhelming inhibitor to useful discussion. The Boosting Resilience programme has been working to support arts and cultural leaders to foster a better understanding of, and confidence in, using their creative assets as well as their IP rights. As we know however, copyright, trademarks and design rights are less likely to generate excitement and more likely to inspire feelings of confusion, uncertainty and dread. Especially when those intellectual property rights are at the heart of a new venture.

“I worry when I see great work created in a collaboration without any sense of it belonging to those creative people”

IP expert Ruth Soetendorp has spent much of her life teaching people who generate IP rights how to manage them. She explains: “Discussing and asking questions is a great way to start learning. But how do you know what to discuss or what questions to ask?”

Getting to grips with IP theory can be challenging for non-experts, to say the least, but it is by no means impossible, and Ruth has developed a bespoke three-stage approach for the programme.

1. Consider other people’s problems

First, she encouraged people to look outside their own organisation to help process problems and thereby put their own into perspective. Ruth has a suite of compelling and diverse case studies to open up conversation and discussion on topics including: how Sydney Opera House is dealing with requests to use its building for advertising; how the V&A dealt with licensing issues when staging the Frida Kahlo exhibition; and how Tate presented a pop-up exhibition at Bicester’s outlet centre.

Such practical and real-life concerns offer considerable opportunities to explore precisely issues that challenge IP managers. When Postman Pat’s creator John Cunliffe died, his obituary was a sobering account of IP opportunities missed or disregarded. Discussing such scenarios gave participants a chance to test their knowledge and sound out ideas on how to approach IP problems.

2. Value personal accounts and case studies

Second, the cohort were encouraged to give case studies of IP issues facing them. Some people brought to the table issues around commercialising their archives, while others were more concerned with systemic issues.

Stephanie Sirr, Chief Executive of Nottingham Playhouse, developed a compelling account of some of the complexities associated with IP in the subsidised theatre sector: “Producing theatre is expensive, returns are hard to predict, and the show that genuinely makes a surplus from scratch is a rarity. It is an arena in which losing money is easier than making it. It is public subsidy and external investment that helps to make a production a possibility and, at a time when the creative industries are booming and theatre ticket sales are buoyant, we need a fair and transparent approach.

“Even if returns are comparatively modest, we need to ensure that part of the financial return is reinvested. This is needed not only to support creative roles, where great ideas and career length may not be infinite, but in the producing structure that enables this to happen. Were cash more plentiful and margins looser, of course, the whole IP conversation would be friendlier and more lucrative for all creative parties.

“However, this is not the case and, in subsidised theatre in particular, IP is often viewed with suspicion. We talk about subsidiary rights – in general taking something and turning it into something else – but are less adept at identifying what IP actually is. Unlike digital media, a recording or a piece of writing, IP in theatre is a combination of finite and subjective elements. It is often hard to exploit without recreating it entirely. Ironically, it is easier when you digitise it for broadcast or similar – then a more accurate reflection of IP is realised.

“The script (royalties automatically paid, quite rightly) might be the starting point but there are many creative voices and creative inputs beyond that. The addition of a director may be, of itself, a major creative decision by a producer. Ditto the choice of a star or genius director that translates ‘dusty’ into ‘zeitgeist’, as well as the actual creative work of making a production with a designer, lighting, sound, choreographer, composer and digital. And the starting point for this creative process is often public money – investment from DCMS via Arts Council England, with no associated mechanism for replenishing that pot.

“A few years ago, there appeared to be a ratio for different elements of the creative process and the idea of a creative producer was not one that was widely exploited. In effect, this probably just meant that even more creative input went unrewarded so I am not advocating a return to that scenario. Collective ventures, where an idea may be devised in a rehearsal room, are similarly viewed as impossible to untangle – but shouldn’t be. We should set out a path from the outset. Devised theatre can be categorised as belonging to ‘The Company’ and then clarity given over what constitutes that company at that moment. I worry when I see great work created in a collaboration without any sense of it belonging to those creative people.

“Speaking up for what you helped create doesn’t make you difficult. You may need a very realistic idea of what that translates to in immediate monetary terms but the principle is key. Truly great ideas are not infinite – most people have a handful across a career. You don’t want to feel aggrieved and exploited. And as a sector we need to find smarter ways to build up financial reserves to ensure that the creative possibilities we exploit today are still available for artists tomorrow.”

3. Know the questions to ask

Third, as Ruth attests: “Finding good answers to solve IP problems comes from asking good questions.” The complexity of the issues that Stephanie describes above gives us some indication of just how important and difficult this is. More than that, it suggests that contemporary arts practice is putting contemporary copyright concepts to the test.

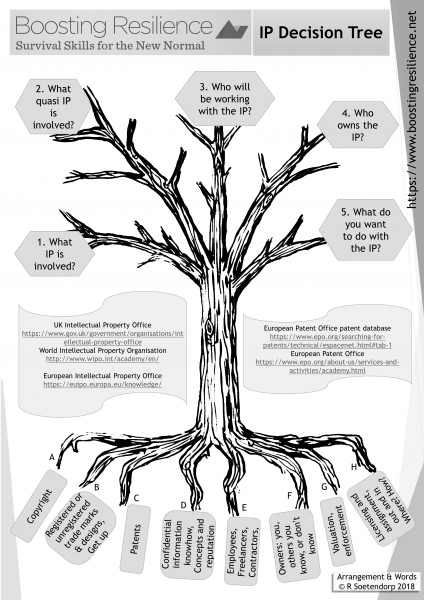

Ruth devised the IP management decision tree above for Boosting Resilience. Its roots are grounded in IP topics – these are briefly described and most readers will have some familiarity with them already. As we move towards the tree trunk, online resources are listed, ready to be consulted. But it is the tree’s branches that are most significant, since they hold the key questions. Designed to be generic and applicable to most situations, the five questions are broad, non-specific and designed to lead to more detailed questions, reflecting the particular nature of a case study or problem. When we used the IP tree, it sparked conversations that were lively, nuanced and sometimes ‘down and dirty’.

Feedback included acceptance that IP is complicated, and as Stephanie’s accounts demonstrate, there is often no single right answer to a problem. There is also no shame in needing to seek out advice from colleagues, online resources or professional advisers. But in using the tree you may find yourself better equipped to take a view on the questions to ask.

The three contributors to this article are: Ruth Soetendorp, Professor Emerita at Bournemouth University and Visiting Academic at the Cass Business School, City, University of London; Stephanie Sirr, Chief Executive of Nottingham Playhouse; and Evelyn Wilson, Co-Director of TCCE and Co-Investigator of Boosting Resilience.

The article, contributed and sponsored by Boosting Resilience, is part of a series on making the arts and cultural sector more resilient.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.