Banksy street art in Boston

Photo: jiva bludeau on Flickr / CC BY 2.0

Tackling class discrimination

By taking a robust approach to understanding the social class make-up of the workforce, the cultural sector can address entrenched inequalities. Dave O’Brien suggests a way forward.

If cultural organisations want to attract a diverse and, in the long-term, sustainable audience, then their workforces need to reflect wider society. Yet there can be little doubt that the arts and cultural sector in the UK is currently not at all representative of the population as a whole. The inequalities in the sector have become its Achilles heel, limiting its ability to retain support from a wide range of communities.

Recognition of this has led Arts Council England and researchers at the University of Leeds to embark on a research project on class and social mobility, and prompted the British Film Institute to present Working Class Heroes, a season of films, talks and workshops celebrating British working class film-makers and helping emerging filmmakers navigate the film industry.

When organisations monitor the equality and diversity of their workforce, the exclusion of certain social classes can be invisible and easily missed

It was also the trigger for Panic!, an AHRC funded project, led by sociologists from the Universities of Edinburgh and Sheffield. This project investigates inequalities in the cultural workforce with a view to starting a more effective conversation about this among those in a position to take action and effect change.

An unprotected characteristic

In England, the Arts Council’s Creative Case For Diversity has shone a spotlight on the unequal representation of women, ethnic minorities and people with disabilities in the arts workforce. It is clear that even if you are gifted and talented, this is not enough to overcome barriers associated with ethnicity, disability, and gender, and this holds true across the rest of the cultural and creative industries.

An important aspect of inequality that has been missing from many discussions is class. This is for a variety of reasons. In equality and diversity legislation, class is not a ‘protected characteristic’ in the way gender, race, disability, or sexuality are. This means that when organisations monitor the equality and diversity of their workforce, the exclusion of certain social classes can be invisible and easily missed. If organisations want to be open to all parts of society they clearly need some way of knowing how they are doing in terms of social class.

At the same time, both in the academic literature and in everyday British life, people disagree about what the term ‘class’ means. As a result, certain social groups may see class as irrelevant or even non-existent. Some of these questions about class are neatly illustrated by the debates and discussions following the BBC’s Great British Class Survey project.

But even though it is complicated and contested, class is an important way of thinking about overall social inequality. It should never be seen in isolation, as it intersects with protected characteristics, such as race and gender.

Origins and destinations

One way of examining class is by looking at jobs or occupations. This is the way that an extensive tradition of social science, and the Office for National Statistics, has understood class.

One reason class is so contested is because it draws together information about people’s starting points in life, and their current social position. We can think of these as origins and destinations. It is class origins that reveal the class diversity of the workforce. Origins tell us the classes people have come from, as opposed to the class of the jobs they do now. In the creative industries almost all of the creative occupations are middle class destinations, yet the people doing those creative jobs might come from a range of different class origins.

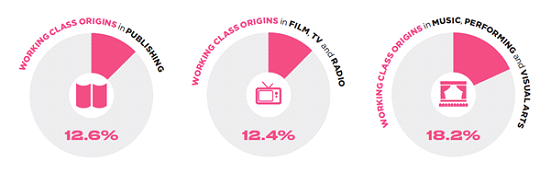

In the report Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries, we highlighted analysis that used data from the Office for National Statistics’ Labour Force Survey (LFS) to understand class origins. We did this to look at the class origins of creative occupations, and found people of working class origin to be underrepresented in specific cultural and creative jobs – fewer than 13% in both publishing and the film and TV industries, and only marginally better in the arts, at 18%.

This is in stark contrast to the 35% of people of working class origins in the workforce overall, according to LFS data.

Occupation-based categories

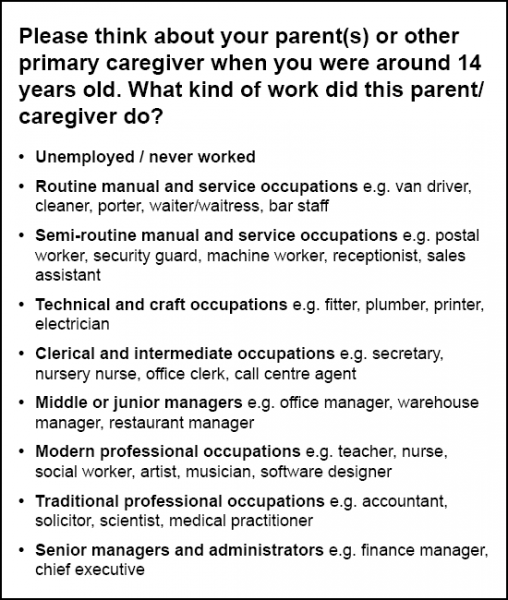

To determine a person’s class, the LFS asks questions about a parent, guardian, or caregiver’s occupation when an individual was growing up. Specifically, it asks who respondents were living with when they were 14 years old; who the main wage earner was at that time; and what their main job was.

This information is used to place individuals on a ‘map’ of occupations called the National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC). NS-SEC clusters occupations together into eight groups, from I (higher managerial and professional, which includes doctors, CEOs and lawyers) to VII (routine occupations such as bar staff, care workers, and cleaners), while VIII is those who have never worked or who are long-term unemployed.

As part of the Panic! Project, we adapted this approach to find out the class origin of creative workers responding to our online survey, adapting and slightly expanding the NS-SEC to give us 9 categories of occupation. Artists, musicians and some other creative industries are classified under ‘modern professional occupations’.

Other approaches

We also asked about parents’ or caregivers’ education, and individuals’ current postcodes, as a person’s occupation is not the only way of describing their class origins. The Cabinet Office has spent several years developing ways of capturing people’s class origins, and this work is a really helpful and essential read for people wanting to know more. They propose several proxies for class origin.

These proxies suggest lots of different questions including, but not limited to, parental income, parental education, the type of school an individual attended, living in an area of deprivation, or being in receipt of free school meals at school.

These measures all have different benefits, but also limitations. For example, it may be difficult for an individual to answer how much money their parents or guardians earned when they were growing up; and ‘growing up in a deprived area’ could be misleading, given that affluent individuals may grow up in deprived areas, but the areas classified as “deprived” have changed over time.

Starting point

Returning to the inequality challenge facing cultural organisations, if they wish to promote diversity in their workforce, then understanding the social class origins of their staff must be part of their thinking.

In order to do this, they should be gathering information on the class origins of their workforce and benchmarking this against other organisations and the rest of the population. Adding a question about class to equality and diversity monitoring and data collection is a good way forward, but this class question needs to be robust.

The occupation(s) of a parent, guardian, or care giver’s while a person is growing up is not a perfect or foolproof measure, as it still needs whoever is doing the analysis to be able to translate occupations into one of the NS-SEC categories, and then again into middle, intermediate, or working class. However, it does provide a well-supported and robust starting point for understanding the class origins of creative workers. Moreover, it removes the tricky problem of self-identification, which various forms of research have shown leads people to misidentify their class position and often their class privileges.

This approach also means organisations can benchmark against the broad trends identified in ONS data; allows them to ask more fundamental questions about social class and how it intersects with protected characteristics found in – or missing from – their workforce; and could change what is on stage, on the page, or on screen. Artistic and cultural responses might then be well placed to go beyond social scientific categories to tell us even more about class and inequality in Britain today.

Dave O’Brien is Chancellor's Fellow in Cultural and Creative Industries at the University of Edinburgh. He is co-author, with Orian Brook and Mark Taylor, of Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.