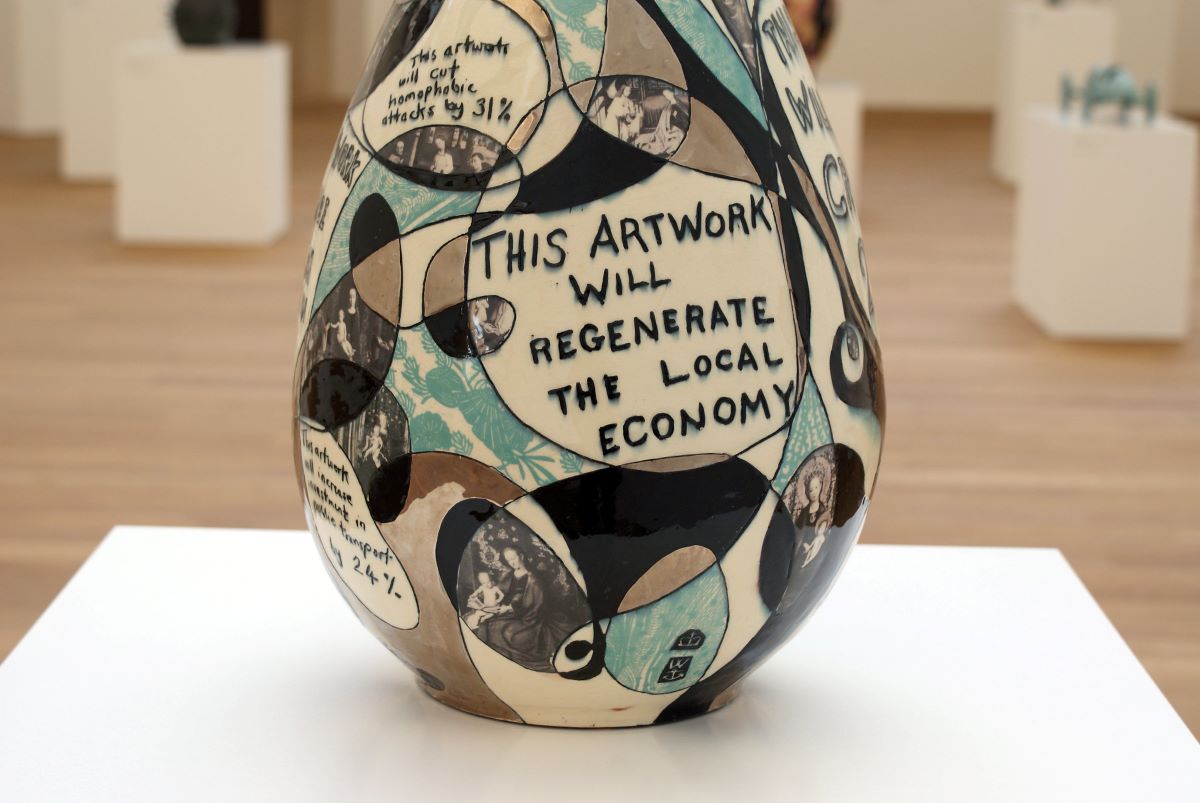

Grayson Perry: This pot will reduce crime by 29% (2007)

Photo: Marc Wathieu/Creative Commons

What have creative practices ever done for us?

Some humanities subjects have been declared obsolete and – by extension – useless areas of education and research. Might creative subjects become subject to the same criticism? ask Patrycja Kaszynska and Brian Ball.

Looking at the last 30 years of cultural policy in the UK, the arts and culture, and by extension the cultural industries, are a fountain of utility.

Starting in the 1980s but amplified under New Labour and up to the present day, the arts are discussed as a panacea. They can take care of regional development, city regeneration and drive inward investment. And they bring a myriad of positive social outcomes such as enhancing social cohesion, and individual-level impacts such as boosting subjective wellbeing.

Indeed, a clay vase by Grayson Perry contains the wry inscription: This Pot Will Reduce Crime by 29%.

Consolidated effort to undermine creative education

Given this claimed usefulness, and the ability of the arts and culture to address a vast array of social and economic ills, why have the practices that sustain them not fared better in recent years?

For instance, as Sally Bacon of the Cultural Learning Alliance has written: “Since 2010, there has been an overall decline of 42% in arts GCSE entries and a 21% decrease in arts entries at A-Level […] more than 40% of schools no longer enter any pupils for music GCSE (42%) or drama (41%), and 84% of schools no longer enter pupils for dance”.

This state of affairs does not come out of nowhere. Rather, it reflects a consolidated effort to undermine the status of creative education, perhaps most aptly illustrated by the ad campaign from the recently departed government to promote re-training in tech, depicting a ballet dancer tying her shoes with the caption: Fatima’s next job could be in cyber (she just doesn’t know it yet).

How can policymakers have it both ways?

Are the creative and expressive practices useful or not? A lot is at stake here, including the spuriousness of the advocacy-led rhetoric about the ability of the arts and culture to single-handedly deliver a dizzying array of outcomes. There is also a failure of the economic and social arguments made to convince decision-makers. And there are the questions about the ground of decision-making itself.

As Robert Peston, the then BBC’s Economics Editor, once queried: “If we could demonstrate conclusively that the economic impact of the arts was zero, would we stop children from learning to draw?” Presumably not. But why?

This is a cogent context to ask about the value of creative practices on their own terms, meaning appealing to the sort of values that the practitioners of creative practices care about.

Let’s face it, not many people go into the arts primarily to generate economic impact – even though it does follow – their motivation comes from elsewhere. The question – what have creative practices ever done for us? – is posed from this vantage point.

Occasions for collective meaning-making

Creative practices are those devoted to perfecting the means of expression – symbolic, aesthetic and artistic. This is done through making, design, composition, articulation, etc. What the vast family of creative subjects has in common is using material and embodied practices – practical expertise and technical skills – to communicate.

Unlike riding a bike or gardening, creative practices result in artefacts – both tangible and intangible – that are about something, and this aboutness makes them conveyors of meaning. More than that, they are occasions for collective meaning-making, as the messages conveyed are not fixed but open to interpretation.

Indeed, much of the technical expertise and making skills in creative practices is devoted to capturing attention, triggering excitement and, in short, making the moments of interpretation engaging, captivating and prolonged.

So, what good is all this collective meaning-making?

We can start answering this if we ask: what is it like to live in Gaza at the moment? What is it like to be a refugee? The majority of readers will not have a lived experience of these situations and yet, arguably, they have a responsibility to know.

Can they understand a bit better what is at issue when participating in the Walk with Little Amal or perhaps by reading Prophet Song, or by seeing Kin on stage? These artifacts – products and processes resulting from creative practice – convey knowledge that would be out of reach to most otherwise and perhaps, in the absence of interpretative space, would be too harrowing to grapple with.

Given the value of creative practices in providing a means of communicating experiences across cultural and spatial divides – of putting us into somebody else’s shoes – it is reasonable to ask whether creative practices are also able to support collective imagining.

How can creative practices engage us in meaning-making about the future we have reasons to value? This is what gets some creative practitioners out of bed in the morning. This is what, first and foremost, renders creative practices useful. Going back to the unfortunate ad, cultural policy needs a ‘rethink […] reskill [and] reboot’ to acknowledge this fundamental source of value.

Patrycja Kaszynska is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of the Arts London and a Research Affiliate at Northeastern University London.

Brian Ball is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Northeastern University London.

![]() researchers.arts.ac.uk | arts.ac.uk/canada/what-is-ual | nulondon.ac.uk | nulondon.ac.uk/about-us/

researchers.arts.ac.uk | arts.ac.uk/canada/what-is-ual | nulondon.ac.uk | nulondon.ac.uk/about-us/

![]() @PatrycjaKasz | @UAL | @NortheasternLDN

@PatrycjaKasz | @UAL | @NortheasternLDN

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.