Book review: What Matters?

James Doeser dissects the convictions underpinning Meyrick et al’s contempt for proliferating attempts to measure and quantify the value of the arts.

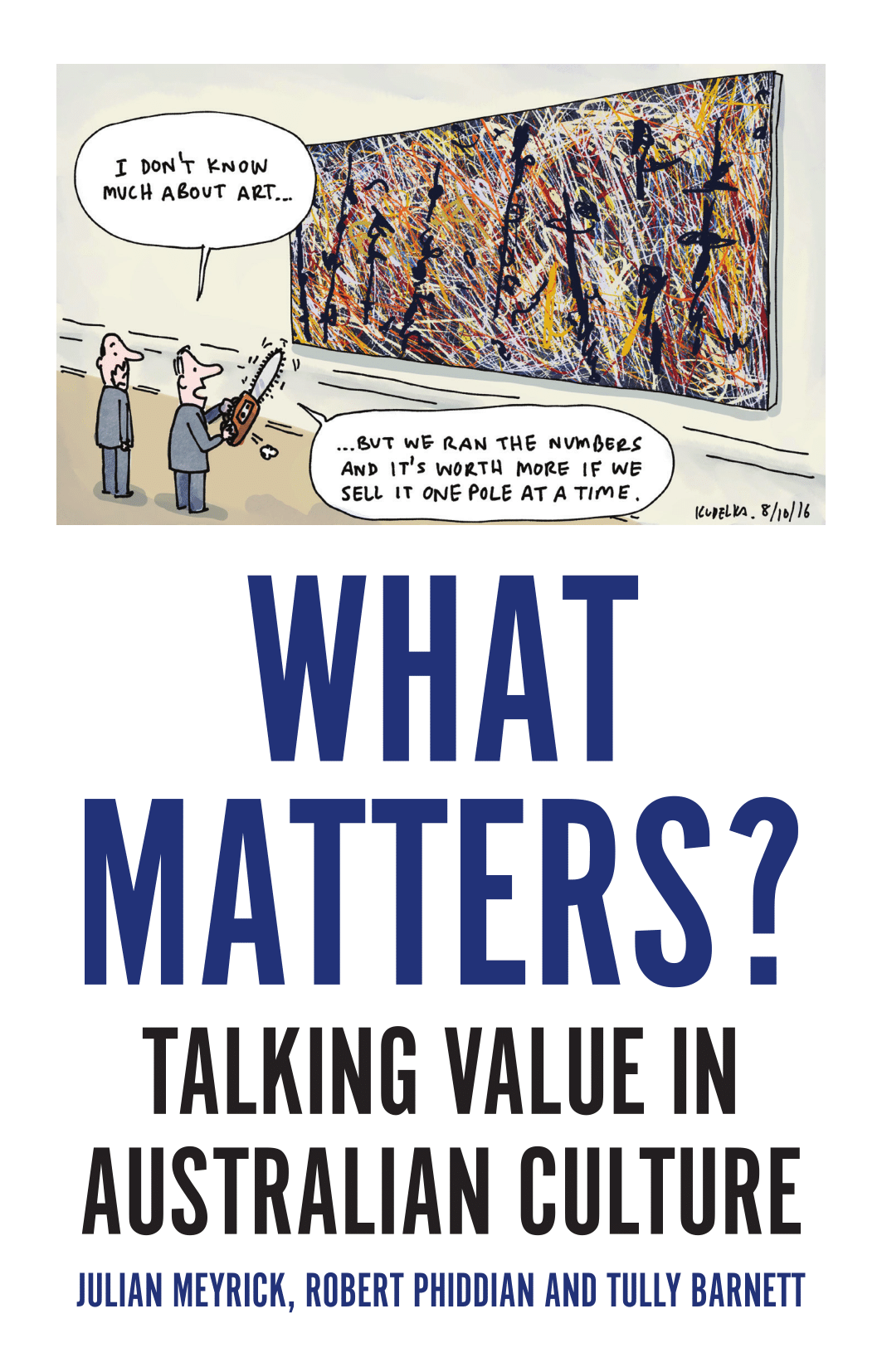

Nowadays you can’t put brush to canvas without the scientists in their lab coats pumping numbers into spreadsheets and producing reductive judgements about impact, quality and value. At least that’s the attitude you’re invited to hold after reading 'What Matters?'.

Our sector is like any other, with hack consultants willing to lobotomise themselves and flatter their client so long as the price is right.

It’s true that measurement and quantification have become more prominent in the world of arts administration. The development of low-cost data collection methods alongside a panoply of theoretical advances have provided researchers with ever-more convenient ways to study the impact and value of the arts. Simultaneously there has been a growing demand on public bodies to be more accountable, in more rigorous ways, in order that they might demonstrate the value that they offer to tax-payers and others with a legitimate interest.

The value of measurement

There has been a lot of effervescent resistance within the arts to these trends. For some it presents yet another layer of bureaucracy in the artistic process, another exhausting bit of friction in the process of getting work made. For others there is a principled objection to the very concept of measurement. They argue that art is irreducible, especially to numbers. It’s hard to tell sometimes whether 'What Matters?' is a defence against the use of scientific methods per se, or a particular set of uses that derive from a particular set of political beliefs about culture and the public good.

There is good faith measurement and there is bad faith measurement. Good faith measurement is an attempt (however flawed, however misguided) to investigate the impact and value of culture and cultural engagement. By contrast bad faith measurement is a cynical attempt by special interest groups to confect evidence that supports their a priori position. The arguments against bad faith measurement are nothing to do with arts and culture and everything to do with cowardice and corruption. Our sector is like any other, with hack consultants willing to lobotomise themselves and flatter their client so long as the price is right. So much for bad-faith measurement. Debating the merits of good faith measurement is a far more interesting conversation to have.

At the very heart of 'What Matters?' is an unshakeable conviction that art is something exceptional, something apart, something outside the everyday commodified material culture that’s all around us. Time and again the authors seem very confident not only in the truth of their perspective on this but that it also reflects a wider public consensus. I’m not so sure. There is some heavy philosophy and sociology out there to help you navigate this issue, but put simply it’s perfectly obvious that these days one person’s tin of soup is another person’s masterpiece. You don’t need Andy Warhol to spell this out for you.

Deficient alternatives

All this intellectual critique might leave you wondering what solutions exist to administer public funding for the arts without resorting to metrics and measurement. There’s a good deal of sympathy in ‘What Matters?’ for Brian McMaster’s short-lived policy of 'Supporting Excellence', which will be very familiar to ArtsProfessional readers in the UK. McMaster made some very appealing suggestions about prizing expert judgement and taking due care to support talented people producing excellent work. This proved useless to Arts Council England: an agency charged with disbursing funds on behalf of the public in a transparent and accountable way.

McMaster recommended that funding decisions be made in ways that meet with endorsement from the arts community. But they’re not the primary stakeholders of a federal arts agency: the tax-paying public is their master. We had The Arts Debate ten years ago in order to discern the public’s preferences. Some of which were enacted in ACE’s priorities and procedures, while other more fundamental parts were ignored. This kind of political disregard for evidence and data sets my keyboard ranting in motion. The same is true for my Australian peers.

The authors of ‘What Matters?’ were motivated to write the book after an egregious and frankly bizarre chain of events in the public administration of Australia’s Arts Council. It’s a story worth looking up. In short, the Arts Minister raided the budget of the country’s arms-length Arts Council in 2015 in order to fund his own pet arts agency. It was a national scandal. For arts advocates it brought into clear focus that raw political power was immune to all appeals, not only to the minister’s more enlightened self, but also the way that facts and figures (accumulated at great expense in time money and effort by a sceptical but pragmatic arts sector) were deemed completely inadmissible.

What really matters?

Maybe our sector has become overly obsessed with a wasteful parade of meaningless stats and empty claims which, when it comes to the big decisions, prove to be without consequence. But amidst all the bullshit there are more than a few of us (clients and contractors, academics and artists, activists and policymakers) who are engaged, as best we can, in the pursuit of scientific knowledge about whatever we currently choose to call art. It’s good work that serves the proponents of social justice and good governance. In the end, that’s what matters to me.

James Doeser is a researcher, writer and editor.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.