Pulse report: Ethics in arts sponsorship

Following protests of arts organisations’ decisions to accept money from controversial businesses, ArtsProfessional’s latest survey reveals the sector’s perspective on ethics in fundraising.

As pressure on arts organisations to raise funds privately increases, the issue of ethics in arts sponsorship becomes an ever more challenging one. For years the UK’s major museums and galleries have quietly ignoring increasingly loud and creative public protests of their relationships with oil giant BP. And, more recently, an artist boycott led arms manufacturer BAE Systems to back out as one of three key partners of the Great Exhibition of the North.

This ground-breaking research by ArtsProfessional has gathered the views of the sector on whether – and if so, how – arts organisations should embed ethics in their fundraising strategies, and how they are making decisions right now.

The survey ran from 26 March to 9 April 2018, was distributed among readers of ArtsProfessional and received 589 complete responses, nearly all from people working in arts or cultural organisations that are open to receiving sponsorship or major gifts, some of whom rely on these as a major income stream. Respondents represented a broad range of artforms, from dance and music, to theatre and museums.

Read the full survey responses in the pdf document here, including almost 1,000 comments related to ethics in arts sponsorship.

Ethical positions

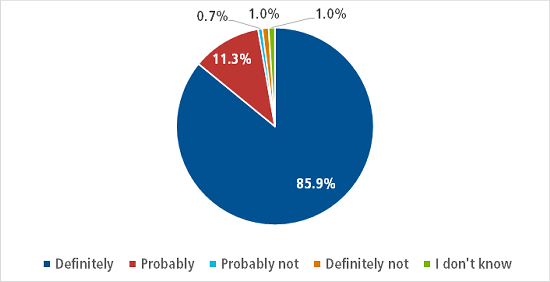

It is an almost universal view among arts workers that arts organisations should take the activities of their potential sponsors and major donors into consideration when deciding whether to accept support. Almost all respondents said they thought arts organisations should definitely or probably do this.

Should arts organisations take into consideration the activities of potential sponsors and/or major donors? |

|

In their comments, respondents pointed not only to ethical concerns, but to the legal and reputational risks involved in accepting financial support from the wrong person or organisation.

“When you associate your brand with another brand, you will inevitably be linked with their ethics and business practices.”

“It can be a risk to the organisation if a sponsor or major donor is involved with illegal activity, money-laundering or human rights abuses.”

“The reputation of an arts organisation is one of its key assets. Any activity – real or perceived – which could damage that reputation must therefore be considered carefully.”

Some raised concerns about arts organisations facilitating what has been branded ‘artwashing’, when organisations with poor public reputations give money to the arts to help ‘clean up’ their image.

“Branded sponsorship is not an altruistic approach to arts and cultural funding but has commercial or political benefit to the sponsor; if the sponsor or donor conducts damaging activities for society or the environment then arts organisations are at risk of complicity and effectively dressing unethical activity as acceptable in the public eye.”

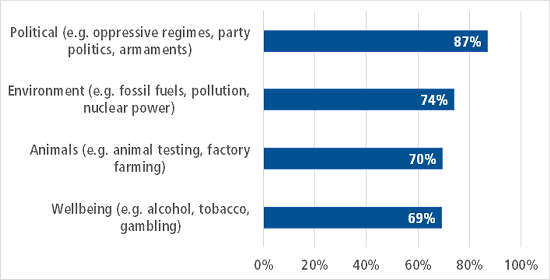

When asked about ethics in relation to specific activities, most respondents agreed that arts organisations should consider refusing support from organisations or individuals associated with political activities (e.g. oppressive regimes, party politics, armaments), as well as those that have a negative impact on the environment, or the wellbeing or people or animals.

Should arts organisations consider refusing support from sponsors / major donors associated with activities in the following areas? |

|

However, many pointed out that these categories are too broad and that they would, for example, differentiate between fossil fuels and nuclear energy, or animal testing used for cosmetic versus medical purposes. They also emphasised that clear lines cannot be drawn, and being able to make decisions on a case by case basis was key.

“Depends on the level of gift and what they are expecting in return.”

“An orchestra might be happy to accept sponsorship from an alcohol manufacturer for a concert or for chair sponsorship of a musician etc. but might not be happy to accept money from the same source to support their work with children and youth.”

“I believe it’s about weighing the risk and ethical impact on the organisation against the value that the sponsors and donors are providing – is it worth the money?”

Individual respondents pointed to many other activities that they would consider cause to refuse support from a donor or sponsor. These included poor employment practices; tax avoidance; banking; manipulation of the media; production of fast food; preaching of religious fundamentalism; promotion of inequality; “social cleansing” (e.g. by property developers); and pornography.

Some respondents said it was down to each individual organisation to ensure its values and goals align with those of its supporters, while others took a broader view, believing that because the arts exist to improve lives and society as a whole, it would be hypocritical to become involved with organisations that do the opposite.

“This is down to each particular arts organisation and what its ethical code is, along with the perceived ethical codes of its audience.”

“The vast majority of arts and cultural organisations (especially those that are charities) cite mission purposes that include some element of a desire to affect positive social change. As such, it would be unethical to accept money from an organisation or individual whose activities were in contravention of that purpose.”

Concerns were raised about the pervasiveness of unethical practices, and the hypocrisy of labelling some money as ‘bad’ in a capitalist society.

“All the organisations involved in these activities will pay taxes and therefore all donations you accept from them will be ‘tainted’ because we live in a capitalist society. No one’s hands are clean.”

“Where do you stop. Do you start by asking the patrons where they work and who pays their wages?”

“I personally grapple with the ethics of accepting donations from certain sources. However, anecdotally, I find my peers are happy to overlook such issues in the belief they are ‘Robin Hood’ figures taking from the rich to give to worthy causes.”

Some questioned how arts organisations come to ethical judgements, and whether it is acceptable to base these on the values of individuals rather than trying to represent the ever-shifting views of society as a whole.

“Is there public consensus around the ethics of the activity that the sponsor carries out? It is important to look across the whole of society and not the organisation’s own immediate echo chamber to make this judgement.”

“Only recently have we considered tobacco is bad, lots of people smoke. The same with gambling, the Government allow adverts on the TV. We have all been polluting.”

Vulnerabilities of arts organisations

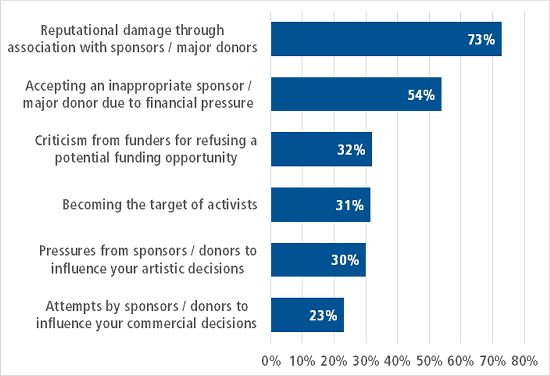

There are widespread concerns that arts organisations are vulnerable to reputational damage through association with a sponsor or major donor whose own reputation is subject to criticism. More than half of respondents also thought their organisation might feel forced to accept support from an inappropriate sponsor or donor due to financial pressure, and a third thought refusing support may lead to criticism from other funders. Less of a widespread concern was that a supporter may influence artistic or commercial decisions.

Is your organisation vulnerable to any of the following? |

|

Respondents shared anecdotes and pointed to media stories of arts organisations suffering reputational damage, or being coerced by a supporter into making damaging decisions.

“The reputational damage caused by an association with certain companies/donors could be detrimental to the charity and outweigh the benefits of the income from the sponsorship/donation.”

“Sponsorship from corporations that have other interests such as shareholders can lead to censorship of artwork and influence which artists are shown in institutions.”

“I have worked on a festival which was ultimately destroyed by the influence of major sponsors.”

Many respondents pointed to a lack of time, money and resources as a key factor in their organisation’s vulnerability to accepting support from an inappropriate source.

“As funding becomes tighter and more competitive there may unfortunately become times where acceptance of support becomes necessary.”

“The issue is that a small organisation doesn’t necessarily have time and resource to conduct extensive research into the ethics of a potential sponsor or donor.”

Policies and practice

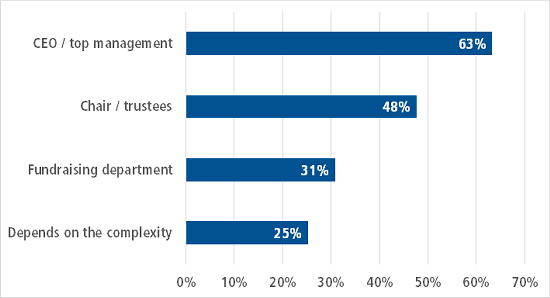

Decisions about accepting sponsorship or major donations most often involve the CEO or top management and around half of respondents said trustees would be involved. Although a quarter of respondents said it would depend on the complexity of the decision.

Who is normally responsible for a decision about accepting sponsorship or a major donation? |

|

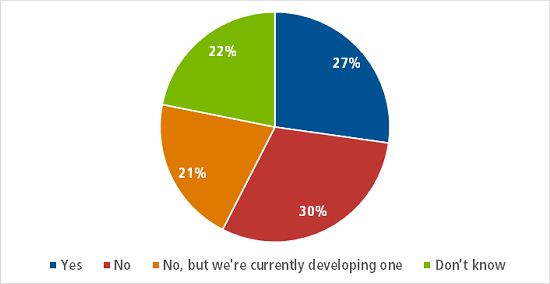

Policies that guide ethical decisions relating to sponsorship and major donations are still quite rare in arts organisations – only just over a quarter of respondents said their organisation had one. A fifth are in the process of developing one, although of these just 40% said there was sufficient advice and guidance available to help them do so.

Does your organisation have a policy guiding ethical decisions relating to sponsors and/or major donors? |

|

The majority of respondents said they saw the value in having a policy to guide decisions relating to sponsorship and major donations.

“Arts and cultural organisations need to be clear, to themselves and their external stakeholders, about their value proposition. When they understand their vision, mission and values they are in a much better position to make decisions about who to form relationships with…”

“Deciding on the moral or ethical ramifications of any significant donation is always going to be a far more complex/nuanced issue than can be neatly fitting into, and fully explained by, an ethical fundraising policy. But the policy is important and every organisation should have one nonetheless.”

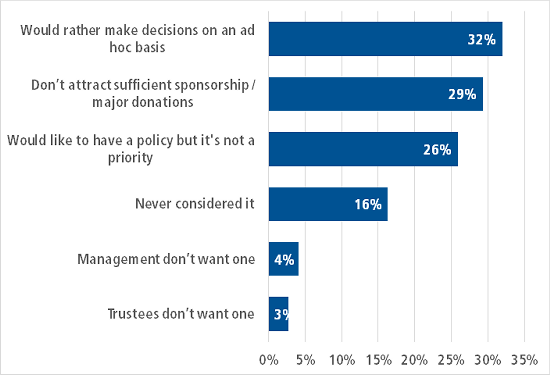

The most common reason for not having a policy was that an organisation would like to be able to make decisions on an ad hoc basis – around a third said this was the case. Another common reason was that their organisation didn’t attract sufficient sponsorship or donations for a policy to be worthwhile. Just over a quarter would like a policy, but said it wasn’t a priority at the moment.

Why doesn’t your organisation have an ethics policy? |

|

“We decide on a case by case basis if there is any controversy.”

“As a small company, we only ever make direct approaches to sponsors/donors whereby we’re familiar with the people we approach and their work.”

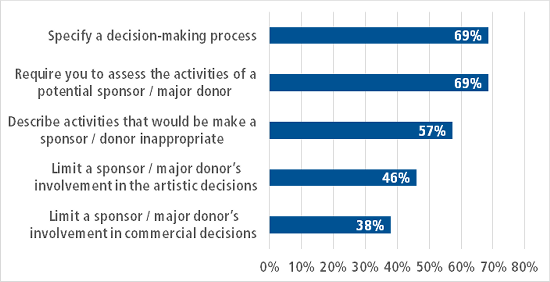

In organisations where policies are used, they tend to specify a decision-making process to follow to assess offers of sponsorship or major donations. They also often describe what circumstances would make an offer of support unacceptable or what activities would make a sponsor or donor inappropriate.

Which of the following does your policy do? |

|

More than half said their policy would not allow them to accept sponsorship or a major donation from a supporter involved in political activities (68%), or activities that had a negative impact on the environment (53%) or people’s wellbeing (59%). Less than half (43%) said it made specific reference to activities harming animals.

“The worry with having a policy is that people don’t want to restrict future opportunities so the policy is lenient and open to interpretation.”

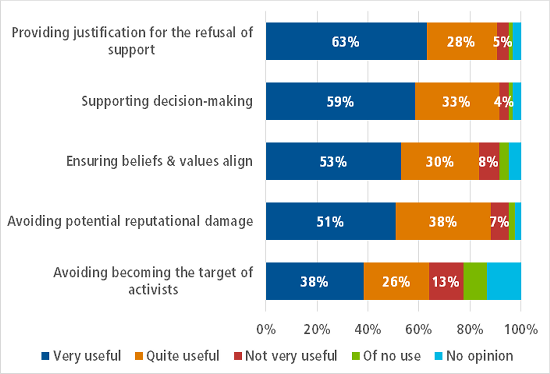

Of those with policies in place, the vast majority said they were either very or quite useful in supporting decision-making. They also provide justification for refusing sponsorship from an inappropriate potential supporter, and help arts organisations to avoid reputational damage.

How useful is your organisation’s policy for doing the following? |

|

Despite this positivity, those working for an organisation with a policy were still just as likely to believe their organisation was vulnerable to reputational damage through association with the wrong kind of supporter. They were, however, less likely to think their organisation would accept support from an inappropriate supporter due to financial pressure: 38% thought this was a risk their organisation faced, compared with 60% among those who work for an organisation without a policy.

Some were troubled by what they saw as a prioritisation of their organisation’s reputation over its ethics and values.

“The main concern is regarding reputational damage rather than any ethical concerns.”

“The question around reputational damage is troubling. If we refuse support not because we think the donor unethical, but because we are worried about ‘reputational damage’ then that in itself is an unethical decision.”

There were calls for larger organisations to take a lead in guiding ethical fundraising practice, and to support debate.

“It’s the larger, nationally and regionally leading organisations who receive the larger donations and deserve the greater scrutiny. They are also the most able to move fundraising efforts elsewhere and set a declared and strong ethical example for the sector.”

“I would like to see a legal requirement for organisations with a turnover of over £250,000 per year to draw up and publish their own Donations and Sponsorship Policy.”

“A worrying trend is that many cultural organisations who have faced controversy in this area resist transparency and accountability around their decision making… An important first step is to have a more open and informed debate – panel discussions and published policies/processes can all aid in doing this.”

Conclusion

While there is a clear imperative for arts organisations to weigh up the risks and rewards before accepting a sponsorship deal or major gift, the findings of this survey reveal there is a split in opinion about what motive should underline this decision-making process. Should they take the opportunity to ‘turn bad money into good’ so long as it doesn’t cause reputational damage or impede the delivery of their goals? Or do arts organisations, particularly charities, have a fundamental duty to work for the public good?

Nearly every respondent who works for an arts organisation indicated that they do accept sponsorship and major gifts, but the fact that just 27% of these were aware of an organisational policy that guides ethical decisions suggests that sector thinking on this topic is still in its early stages. As the push from funders to raise more money privately increases it is only going to become more pertinent.

It is clearly difficult to draw ‘red lines’ – there are no universal ethics and decisions must depend on circumstance. But the risks of getting it wrong are great and every organisation that accepts sponsorship or major donations must take an informed and strategic approach to doing so. The only obvious starting place is more open debate and transparency, from all parts of the sector.

MuseumHour will lead a Twitter conversation about the ethics of sponsorship on Monday 30 April, 8-9pm.

Download AP Pulse: Ethics in arts sponsorship full report (.pdf)

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.