Re-inventing the gallery

Prime Studios in Windsor is a space for artists to work, interact and display their art. Dan Eastmond explains why he wants it to be different.

A few months ago, following a tip-off from a local councillor, a little bit of pushing and a sympathetic ear from a local authority officer, I stepped inside a damp and dusty empty office block that sits under the weight of a 1960s low-rise block. It stank. Six years of emptiness, several leaks that had rotted the carpets and four toilets straight out of Trainspotting made the air inside sickly sweet with neglect. Dead flies lay in rows on every window sill like little tiny exhibits. “This is the place,” I thought. “This is the place we’ve been looking for.” And with that, Prime Studios was finally born. It was conceived a good couple of years earlier, most likely on the fireside rug of lessons learned when Ella Gibbs and I set up Cornershop Studios all the way back in 1992. Then, we just wanted somewhere to work, alongside other artists who shared our aesthetic and social ideas. We wanted a space where we could try out different ways of making things, new ways of showing what we had made, and a place to throw the occasional massive party. We did all of that, it became much more than we expected and the building is still a home for artists and ideas today.

One of the most powerful experiences Cornershop provided was working alongside such a vast range of different creatives. Potters and animators, performance artists and saxophonists, all busying around the same space, feeding off each other's successes and failures. Prime Studios puts this positive contagion at the heart of its structure. It is a curated programme, meaning we pick who goes in, making sure that the space is balanced, that participants are supported and challenged, and that the under-priced spaces benefit people and projects that would otherwise struggle.

There is no point in supporting emerging artists and cultural operators if our institutions can't handle the results

Affordable spaces, as important as they are, are not the whole story. Like the food banks that are popping up in every empty youth club and leaky church, these are symptoms not solutions. I have said it before, but it is always worth saying again: artists should be minted, we shouldn't need cheapo spaces to house our cultural ambitions. We shouldn't need meagre Arts Council England handouts that change nothing, in exchange for hours and hours of form-filling and a bullying hand in our operational practice.

So Prime participants don’t just get a roof over their heads, they get mentoring as well − whatever we can offer that makes sense for them, building business models, finding new audiences and customers, cross-checking ideas and making alliances. They also get access to our performance and exhibition spaces at the Firestation. Not just because it makes perfect sense for their work to feed into ours, but also because there is no point in supporting emerging artists and cultural operators if our institutions can't handle the results.

This is where it gets interesting. The real story of supporting emerging artists. The truth is, we will always be ‘supporting’ emerging artists, forever offering just the edges of opportunity, until we completely overhaul our cultural spaces and create an industry brave enough to bend and break to the demands of new artists, and the audiences they already have.

This is why Lemonade Gallery takes up a third of the space at Prime. Lemonade Gallery has a mission to reinvent entirely how galleries work in the twenty-first century. Why? Because galleries are otherwise so boring. They paint themselves white in pretend neutrality, while engineering their status with structural singularity and in-print critiques from cultural border guards. Galleries hire meat-heads to ring-fence shiny artworks, to make the money feel at home and the plebs know their place. Galleries turn off the music, because this isn’t Urban Outfitters, right?

Well maybe not, but I know where I would rather be, and so does almost everybody else. While most galleries were chipping graffiti off walls or building black boxes to put TVs in, modern retailers were making an art out of engagement and the numbers speak for themselves. Oxford Street, one of the busiest high streets in Europe. Any galleries on it? Nope.

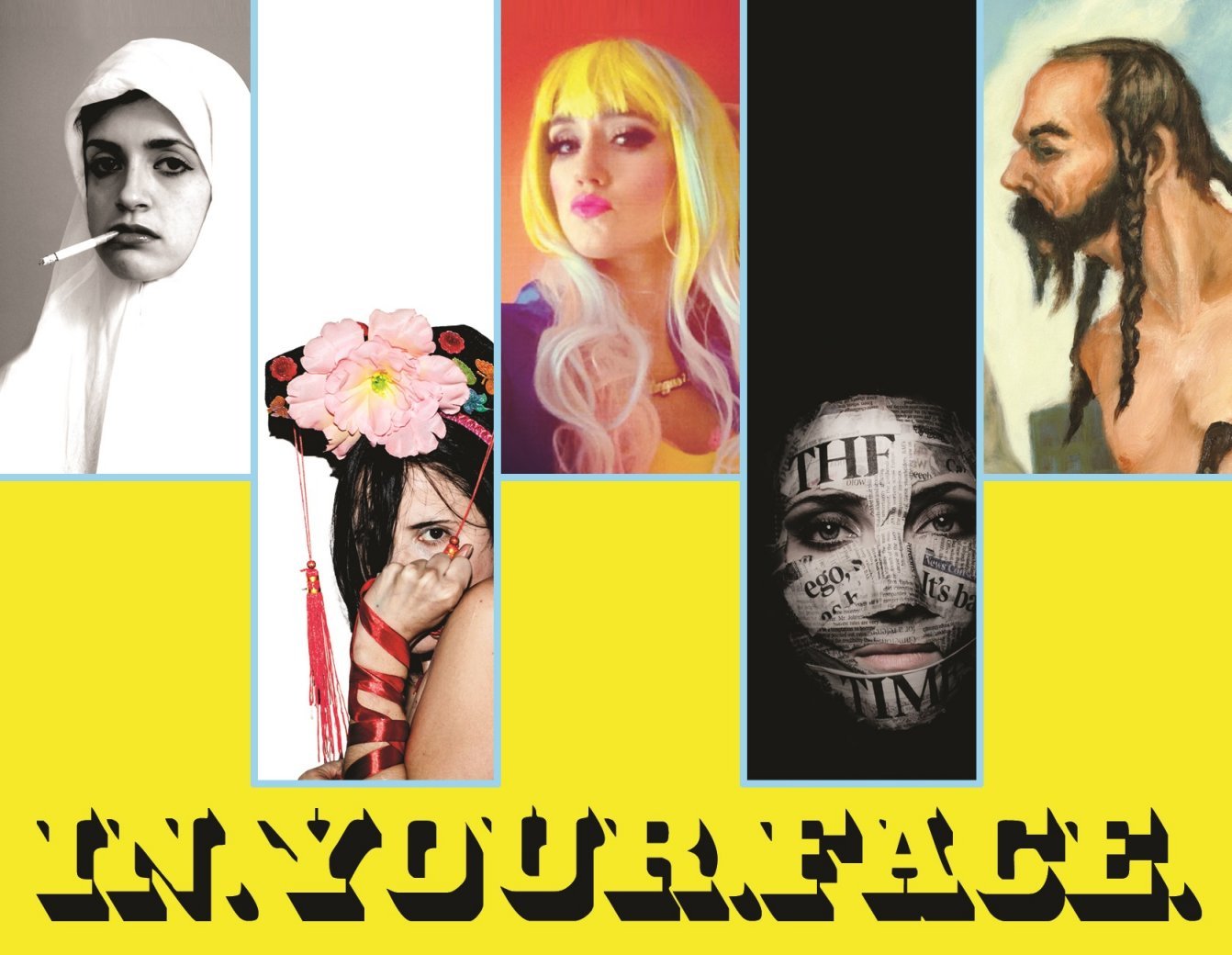

So Lemonade Gallery is working with a small number of European artists: Christo Viola, Csaba Kis Róka, Meg Mosley, Sarah Maple and Syl Ojalla. Their work ranges from oil paintings to animated gifs, on new ways to share, distribute and sell artworks. Their work is provocative, sexy, relevant and exciting, so Lemonade’s job is to keep up and be the same.

Already the questions bubbling up are exciting, from the sorts of technology we use, to which bits are the artworks, to why we are even bothering with a space anyway. The last one is a beauty, seeing as we have not even opened the doors yet, but it is the best of the bunch and one we should ask every day.

In fact, one of my favourite interview questions is always “What is the point?”, as it cuts to the heart of the matter super-quick. Most arts organisations, spaces and creatives should probably ask it every day, perhaps over a champagne breakfast, and certainly when we talk about supporting emerging artists we should just cut straight to it. If you can’t come up with an answer that involves only doing it once, you are doing it wrong.

Dan Eastmond is Managing Director of Firestation Centre for Arts & Culture.

www.firestationartscentre.com

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.