Photo: Ramón Salinero on Unsplash

Reworking what you already have is the opposite of innovation

Covid-19 has proved that what worked back then won’t work now. Patrick Towell says true innovation requires attention, collaboration, and a sense for ideas that can be scaled up for success.

Our studies on resilience for Arts Council England and National Lottery Heritage Fund in 2018/19 emphasised cultural leaders’ understanding of the need to prioritise ‘bouncing forwards’ towards a ‘new normal’ rather than just bouncing back to what had gone before. The times that we found ourselves living through mere months later proved them very right indeed.

While it is hard to be optimistic right now, it’s important to try reframe our challenges from just overcoming adversity in a grimly determined way to spotting and exploiting the new opportunities that external change brings. New business start-ups in the pandemic – many run by millennials – are being founded at an unprecedented rate in the US, at least. Will immediate recovery and future growth in the cultural sector end up being dominated by social enterprises? These enterprises may address new markets with different leisure, learning and entertainment services rather than traditional non-profits with small (perhaps ‘digitised’) versions of their existing offers.

Leading the charge for change

It is obvious, but still worth stating, that strategy development and business planning are about the future. And yet often strategies and plans are so often a recut version of what has already been. This is the antithesis of innovation – assuming that the existing model is right enough to tweak rather than going back to first principles. Now more than ever, the operating environment for cultural organisations is not going to be like that of the past.

So, as those leading change, we need to be both forward looking and externally focussed. Most of the change we are responding to is happening in the wider worlds of society, economy, politics and technology, rather than on our arts, culture or heritage patch. Many of the innovations we may wish to adopt will already have appeared in some form in another sector. Obvious candidates include:

- tourism and hospitality – including non-cultural visitor attractions

- sport and leisure

- digital entertainment and other technology businesses

- health, care and wellbeing services – including use of care budgets alongside social prescribing.

Innovation versus creativity

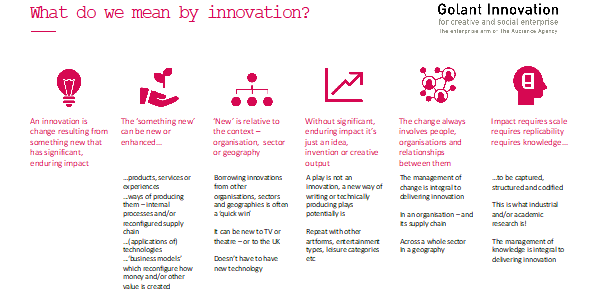

At The Audience Agency, our work across creative industries – including arts, culture and heritage – often involves defining, explaining and discussing ‘innovation’ as a term.

History tells what the true innovations are: changes resulting from something new being introduced with significant, enduring, and positive impact. It is a post-hoc judgement. At the time, all we see are new things driving or enabling change. And if we’re busy creating the new things, we may be tempted to overestimate the extent of change they are creating. We might also overestimate the scale, persistence or rapidity of the resulting impact and its beneficence.

We have discussed before – though it is worth revisiting – how ‘creativity’ gets confused with innovation. People working in the creative economy are especially prone to claiming much of what they do is innovative. Human creativity is a key ingredient in the process of innovation. It is obviously involved in imaging and creating ‘something new’ that innovation requires. But it also contributes to problem solving in the processes of invention, the management of change, and the capture of replicable knowledge. I like the way the Durham Commission report talks about the wider contribution of creativity to all kinds of work – as well as society at large (section 3, if you have time to look).

There is no ‘out of the blue’

Social media, for example, has had a big impact, but regulators, the public and its creators have been (perhaps wilfully) blind to its pernicious impacts on democracy and pluralistic debate. Growing understanding of the negatives may leave many in culture not wanting to dance with the devil of social media. And yet for many segments of the population, social media has become the only realistic means of engaging them in new forms of culture, leisure and entertainment. So, dance with the devil we all must, but in a way that doesn’t conflict with our values and contributes to some broadly Reithian principles regarding the growth of human knowledge and mutual understanding.

Media technologists have been foretelling the death of the traditional cinema film release for more than a decade, but it has taken Covid-19 to shift this conversation from fringe activity to widespread reality. Creatively minded people and organisations – and the policymakers and funders that support them – have historically focussed on digital technology’s impact on production. But scaling potential new service offers or business models (see Heritage Fund’s proposed innovation accelerator) for digital content and experiences requires transformation in distribution as well. This longstanding bias of digital funding and policy towards production unfortunately means that research and policy development at the intersection of digital distribution and culture is slight. What does exist is overwhelmingly dominated by the performing arts, with heritage as a vanishingly small sub-sector.

Elsewhere in media, the UK is experiencing an unprecedented boom in TV production. This is being driven not only by Netflix and Amazon’s investments, which dwarf those of terrestrial broadcasters, but also their use of data to define niches and qualify future hits. Quite what the impact will be on British culture is hard to say. The dominant representations of the UK’s history will be very much more The Crown than the Queen’s Speech, Bridgerton than Downton Abbey – and we would argue that this matters. Our culture is strongly determined by the media we consume. Never again will the UK’s public service media be in the control of a few executives at the BBC, Channel 4 and ITV. The UK cultural sector will ignore this change at its peril.

One size does not fit all

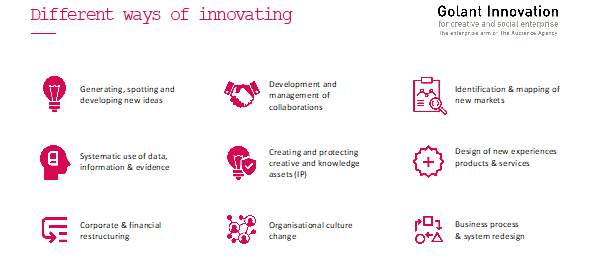

Much of the academic, business and policy literature on innovation concentrates on the key activities of businesses that innovate, be they corporates such as 3M, pharma giants whose purpose is to create and exploit inventions, or start-ups in the Californian venture capital mould. This corporate and investor focus has meant many apply too simple a set of cookie cutter approaches – accessing finance, tech-dominated research and development, and scaling up – to represent what is required to foster innovation.

Our model (above), not perfect or complete for sure, provides more granularity of key innovation activities. While considering these, bear in mind that:

- Raising finance is mostly part of a wider restructuring of finances and the corporate bodies (charities, companies, CICs) that hold them.

- Research into markets, new ideas, or with users is part of a wider systematic use of data.

- Technology development is part of creating a range of knowledge assets alongside creative outputs and management-level knowledge like processes and policies.

Exploitation of IP and scaling up of services and organisations is an alchemy of many different activities. Although it may be helpful to investors, policymakers and business schools to group them in this way, culture’s changemakers need to a more nuanced view. It may be worth looking at potential innovations you’re researching or developing and seeing what range of innovation activities you have planned and resourced.

No success without scalability

Finally, back to scale. Innovation requires it. Many digital services or business models don’t work without it. So perhaps, the most important reframing of your innovation challenges is to not see them as a solution that your organisation can deliver. Instead, the need for scale and investment may mean the solution is only feasible and viable with significant numbers of partners across the arts, culture and/or heritage sector, as well as the wider digital, entertainment, media, publishing or e-learning sectors.

For those who haven’t already spotted it, ACE’s Project Grants are actively encouraging projects with research and development and organisational development. I’m sure we haven’t seen the last of funding from UKRI, Innovate UK, AHRC and the like spanning culture, creative business and other sectors.

I hope this encourages you to dust off some ideas and – with partners that bring scale – secure funding for them. We’ll be talking more about scaling up next month in a more practical piece about how to jump on a good collaboration opportunity when you see one. Until then, think big.

Patrick Towell is Innovation Director of The Audience Agency

This article, sponsored and contributed by The Audience Agency, is part of a series sharing insights into the audiences for arts and culture.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.