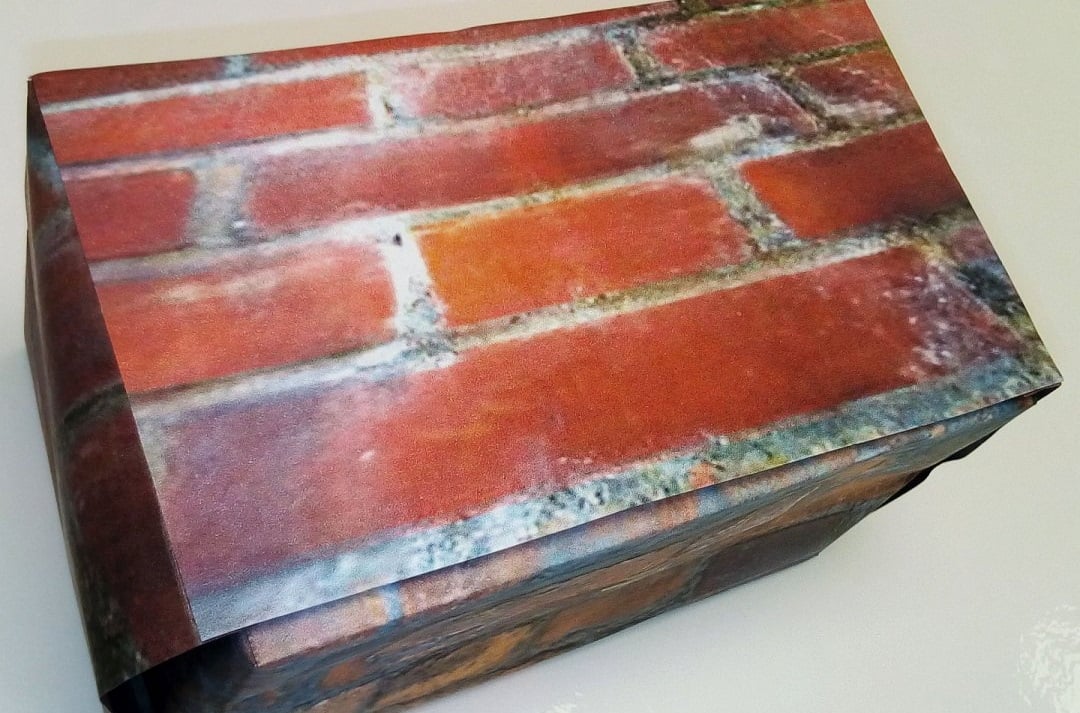

How do you caption a deliberately ambiguous object?

Photo: Eleanor MacFarlane

The craft of captioning artworks

If artists want an authentic response to their work, they need to give viewers a way in, argues Eleanor MacFarlane.

One question eternally asked by artists goes as follows: is what I am putting into this work actually what the audience experiences? And the answer to that will always elicit diverse responses.

‘Untitled’ is not an open door to many viewers, and is in fact a closed door

As an artist myself, I have always been fascinated by the creative process and the mechanisms going on when making, looking at or thinking about work. It’s a form of reflective practice that I took further by taking an MSc in psychology. The learning curve into science was considerable, but I was able to direct my final project back to the arts. I made a study comparing artists and non-artists in a series of tasks about the meaning of objects. Study conditions made my results statistically reliable, and I found differences in how objects are understood.

Research study

My experiment was a series of tasks where participants had a choice in a triad of objects, starting with a scientific standard: What goes in the same category as milk – cow or lemonade? If you choose cow, that’s the thematic choice, because the link is by narrative association in that milk comes from a cow. If you choose lemonade, the choice is taxonomic, because milk and lemonade are only linked by sharing certain physical properties in that they are both liquids.

Subsequent tasks were deliberately more ambiguous, and did not neatly divide into thematic and taxonomic choices. They were mixed, or ambiguous, as objects are in life and in art.

My study included measures for ambiguity. My current, non-scientific, working definition of art would be ‘deliberately ambiguous objects’. After the study, there were conversations with participating artists who thought, or realised, that ambiguity was the key to their art. This is what the art-crit really explores – the thematic, taxonomic and ambiguous properties of work. In other words: is this thing what I think it is, and does it mean what I want it to mean? In even plainer words: does it do what it says on the tin?

It doesn’t matter how abstract or conceptual the art is, these are the fundamental concepts and practicalities artists grapple with in their practice, and by extension, art institutions when they present art.

My study simply provides evidence that artists overwhelmingly access stories or personal memories when deciding what an ambiguous object is, whereas none of the non-artists did. Artists were better able to ‘read’ an object and offer more interpretations, whereas non-artists were more stumped.

Many artists want people to apprehend their work honestly, to encounter it with an authentic response, but my study shows that you have to give people an opening. Artists and galleries have to provide titles, clues, ways in and things to relate to.

Titling and styling

The title, like that of any book or film, gives the first clue to the audience, and is a signpost towards, or away from, what it’s supposed to mean. The title is what’s written on the tin. My research suggests that art should be titled. ‘Untitled’ is not an open door to many viewers, and is in fact a closed door. As an artist, I always thought titling work was part of the fun, and part of the work.

Art institutions should also think less about sticking to a house style, where assumptions are unconsciously adopted throughout. There is no one clear, universal font, and no one style that can cover all bases. Therefore, it makes sense to interpret and caption in a diversity of styles.

What this means in practice is simply shaking things up every so often and loosening up rigidity. Different types of text or layout will speak to someone who has been missed out before. It needn’t be chaotic, only diverse.

Making assumptions

Psychology study results are often counter-intuitive – we don’t always do what we think we do. I have subsequently talked to some participants who assure me they always tell themselves a story when looking at work. I don’t contradict them, but sometimes I remember what their response was and I’ve gone back to check and the results speak differently.

We think we have thought through inclusivity, but miss out aspects beyond our assumptions. We all make assumptions – that’s part of human nature, but arts professionals make art assumptions, and don’t usually see outside that paradigm.

In my career as an artist, I’ve participated in exhibitions, reviewed and written about hundreds, and assessed them for various schemes. I use galleries for meetings with colleagues and students and love to visit them with friends, family or by myself. I’m something of a professional visitor. So I look out for these things, and yet I still find myself sometimes confounded by access, layout and captioning. I’m tuned in, but sometimes it doesn’t speak to me and I don’t get it. And so what of someone who doesn’t really speak the language?

My approach for more diversity would be for galleries and institutions to welcome in the occasional external perspective. If I was a gallery director, I would note the observations of new staff and interns who still have a fresh eye. I would do a walk-through of my space with an outside professional such as a retail expert who specialises in customer flow. And I would invite independent assessors for a ‘does-it-do-what-it-says-on-the-tin’ walk-through.

Eleanor MacFarlane is an artist, writer and researcher.

www.eleanormacfarlane.com

Tw @eleanormacfar

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.