Class influences career entry but not career progression, research finds

Over 70% of respondents now working in music, the visual arts or museums/heritage come from households where the main income earner worked in a professional or senior managerial occupation.

Although people from working class backgrounds are significantly underrepresented in the arts workforce, new evidence from AP’s ArtsPay 2018 survey suggests that their social class is unlikely to be a significant barrier to progression once they start work in the arts sector.

Salaries in the cultural sector also appear to be only loosely related to the socio-economic status of workers.

There is, however, evidence suggesting that careers in music, the visual arts and museums and heritage are less likely to be followed by those from working class backgrounds, and that full-time arts sector employees in London are less likely to be from working class backgrounds than those employed elsewhere in the UK.

Profile

These findings are based on responses from 1,245 full-time employees working in the UK arts sector who gave information in the ArtsPay 2018 survey about the occupations of their parents – a measure that author and academic Dave O’Brien has proposed as a model for assessing social class in the cultural sector.

Only 10% of full-time employees who responded to the survey came from working class backgrounds, while two-thirds were brought up in homes where the head of the household worked in a professional or senior managerial role.

This is in stark contrast to the UK population as a whole, where 35% of people have working class origins, according to the Labour Force Survey (LFS) run by the Office for National Statistics.

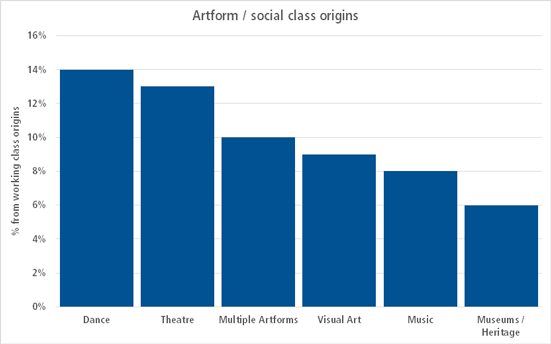

Clear differences emerge between art forms. Those working in music, the visual arts or museums and heritage are most likely to come from households where the main income earner worked in professional or senior managerial occupations when they were young. Over 70% have this background, compared with 61% of employees in theatre and 60% in the dance sector.

The figures also show that 19% of BME respondents are from working class origins, compared with 9% of white respondents; and that women in the sector are more likely than men to have professional class origins (68%, compared with 58% of men).

Location, location, location…

The survey reveals distinct regional differences in the composition of the workforce. Over three-quarters (76%) of those employed in the arts in London are from homes where the main income earner worked in a professional or senior managerial role, while this is true of only half (52%) in the North West. In Yorkshire, the North East, and the East of England, the figure is also less than 55%.

In contrast, the origins of more than one in six full-time arts workers in Northern Ireland, Wales or the East Midlands are in families where the primary earner worked in routine or semi-routine manual or service occupations, or were unemployed or never worked. The equivalent figure for London is one in 14.

Pay gap

But while there are marked regional disparities in the social class profile of employees in the sector, the data reveals that average (median) pay for both groups is broadly similar. Those from professional backgrounds earn an average of £30,000, while those with working class origins earn £29,000. This pay gap is significantly less than the pay gap between genders, with women earning on average £4,500 less than men.

The class pay gap appears to be greater among part-time workers though, with those from the highest social classes earning full-time equivalent salaries of £29,000, compared with £25,750 among those with working class parents.

Progression

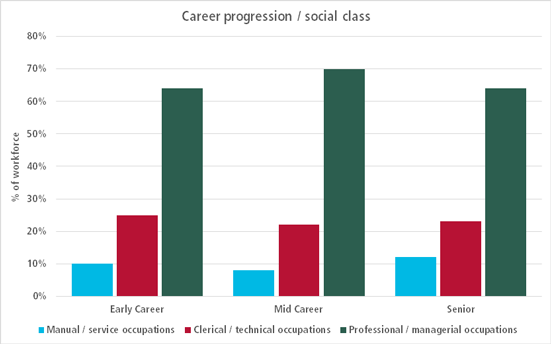

Despite being hugely underrepresented in the cultural sector workforce, people from working class backgrounds appear to be progressing in their careers at the same rate as those from professional or managerial homes. Similar proportions of survey respondents employed full-time have working class origins in early career, mid-career and senior roles.

Again, this is in contrast to the gender progression gap in the sector, where 83% of early career posts are held by women but only 69% of senior roles.

This is the second in a series of articles relating to the findings from the 2018 ArtsPay survey. Findings based on further analysis will be published in the coming months. ArtsProfessional would welcome conversations with academic institutions and other bodies interested in having access to the wholly anonymous data set to conduct further analysis that will shed more light on pay practices in the cultural sector.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.